Revision Resources

Recent Posts View All

November FOAMed

Splenomegaly

A 20-year-old female with no past medical history presents to the ED with “abnormal results” found on a CT scan. She was feeling well until approximately 2 weeks ago when she began to have fatigue, malaise, loss of appetite and abdominal discomfort. She saw her primary care doctor who ordered an outpatient CT scan of her abdomen and pelvis, and upon obtaining the results showing splenomegaly, sent her to the ED for evaluation.

Vitals: HR 108, BP 118/78, RR 20, Temp 100.8F, SpO2 100% on room air. On exam, she has a scaphoid abdomen with a left-sided palpable mass extending 8cm past her rib cage, consistent with splenomegaly. She is fatigued-appearing and tachycardic, but the rest of her physical exam is normal.

What is the approach to the patient with splenomegaly?

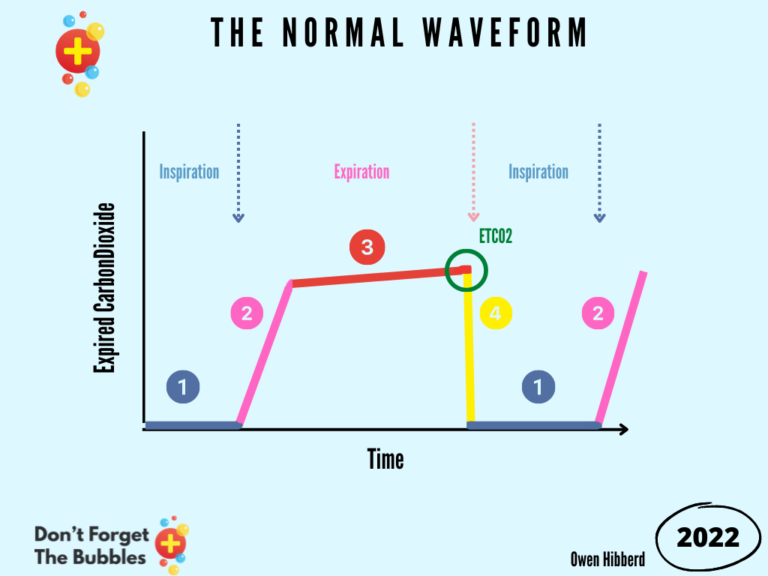

Capnography

Capnography is the measurement of the concentration of carbon dioxide (CO2) in respiratory gas. It demonstrates this graphically via the capnogram waveform and numerically via capnometry. This method offers the advantage of being non-invasive and providing information on arterial blood carbon dioxide concentration (PaC02) as opposed to other methods of measuring carbon dioxide in the blood.

There are also other qualitative methods of detecting expired CO2 which include pH-sensitive chemical indicators that change colour with different levels of CO2.

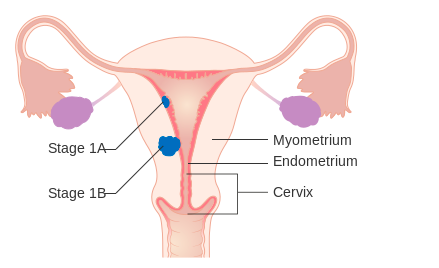

Bleeding Cervical Cancer

A 52-year-old woman with known cervical cancer, hypertension, diabetes type II, and atrial fibrillation on apixaban presents to the emergency department (ED) with heavy vaginal bleeding. She was diagnosed with cervical cancer one year ago and has not responded to treatment, with her most recent CT scan showing metastasis to the liver and lungs. The vaginal bleeding started as light spotting two days ago but has gotten steadily heavier. She now endorses using two pads an hour for the past three hours. Additionally, she has experienced dyspnea on exertion and light-headedness. Her triage vitals are temperature 97.9 °F, heart rate 102 bpm, blood pressure 95/50 mm Hg, respiratory rate 18 breaths per minute, oxygen saturation 98% on room air. On physical exam, she is diffusely tender across her lower abdomen. On pelvic exam, the patient’s cervix is not visualized due to blood pooling in the vaginal vault. Bleeding volume obscures view even when forceps with gauze are utilized. No bleeding source can be visualized. What is the most appropriate step in this patient’s care?

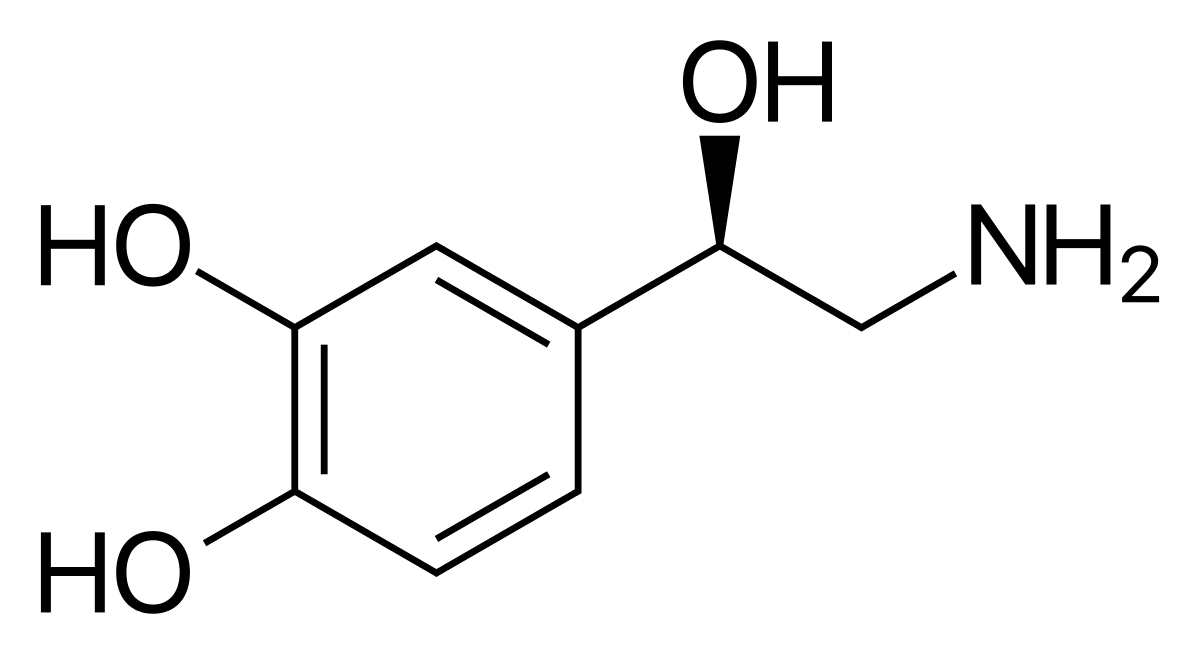

Pressors 101

Pressors, by and large, attempt to improve blood pressure by altering the cardiac output and/or the systemic vascular resistance (BP = CO x SVR). Be aware, however, that perfusion is not as straightforward as a simple math problem. When we increase the systemic vascular resistance, we do not guarantee that the cardiac output will remain constant — if we are asking a weak heart to pump against greater resistance without augmenting cardiac function, we might inadvertently decrease the cardiac output and tank perfusion. However, the counterpoint to that is that vasoconstriction likely also increases preload, which could improve cardiac output. Think of choosing a pressors as a balancing act and consider the underlying pathophysiology of hypoperfusion. Monitor the MAP, but also monitor clinical factors such as urine output, cap refill, and mental status to guide your resuscitation.

Are you sure you wish to end this session?