Revision Resources

Recent Posts View All

July FOAMed

Bleeding Disorders

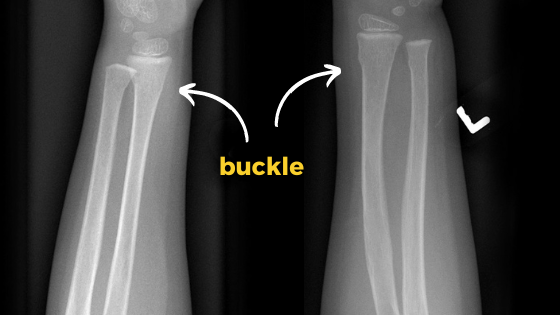

A 23-year-old female with no past medical history presents to the ED for prolonged bleeding from her tooth extraction earlier the same day. Her dentist was planning on removing all her wisdom teeth but stopped after the first extraction due to inability to achieve hemostasis. She has never experienced this kind of bleeding before but notes that recently her gums often bleed when brushing her teeth and describes her last few menstrual cycles as “heavier” than usual. She is not on any blood thinners and was adopted at birth without record of family medical history.

On exam, her vital signs include HR 92, BP 118/78, RR 14, O2: 98% on RA, and 37.1°C. Tooth number 17 appears to have been extracted, and there is blood-soaked cotton balls and gauze between the buccal mucosa and the cavity where tooth 17 used to be. Upon removal of the gauze, you notice a slow oozing of blood from the extraction site. No trismus, sub-mandibular swelling, or other signs of potential airway compromise are present.

What are some of the bleeding disorders on your differential given this clinical presentation?

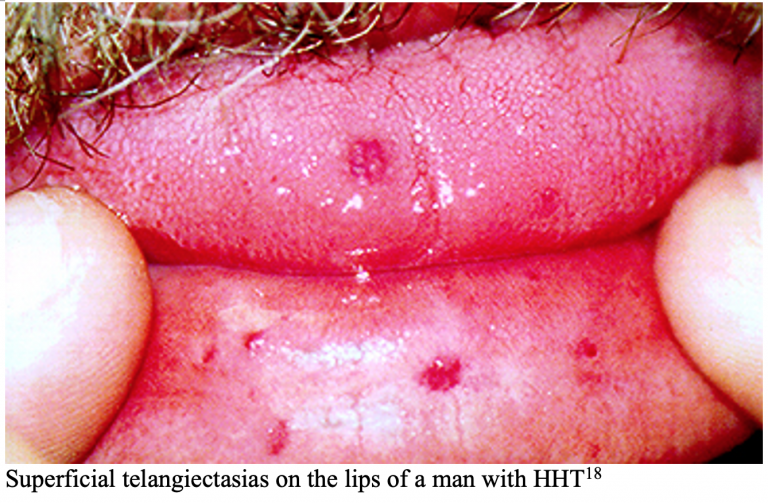

Torus Fractures

Torus fractures (or buckle fractures) are a common presentation to the paediatric emergency department, yet we don’t seem to agree on how best to manage them.

Some of us apply casts, some use splints, some have orthopaedic follow-up, and some have none.

What we do know is that torus fractures heal quickly.

Massive Hemorrhage Protocols

What’s in the name – why “Massive Hemorrhage Protocol” and not “Massive Transfusion Protocol”? In this episode – The 7 Ts of Massive Hemorrhage Protocols, Dr. Jeannie Callum, Dr. Andrew Petrosoniak and Dr. Barbara Haas join Anton in answering the questions: How do you decide when to activate the MHP? How do you know when it is safe to terminate the MHP? What lab tests need to be done, how often, and how should the results be shared with the clinical team? Once the dust settles, what do we need to tell the patient and/or their family about the consequences of being massively transfused? What should be the lab resuscitation targets? Why is serum calcium important to draw in the ED for the patient who is exsanguinating? How do we mitigate the risk of hypothermia? What can hospitals do to mitigate blood wastage? If someone is on anti-platelets or anticoagulants what is the best strategy to ensure the docs in the ED know what to give and how much? Until the results of lab testing come back and hemorrhage pace is slowed, what ratio of plasma to RBCs should we target? What’s better, 1:1:1 or 2:1:1? Should we ever consider using Recombinant Factor 7a? If the fibrinogen is low, what is the optimal product and threshold for replacement? When and how much TXA? Anyone you wouldn’t give it to? and many more…

Hand Injuries

You look at the track board and see that a 36-year-old male has been roomed with hand pain. You may be thinking “Easy, I’ll get x-ray and this guy will be out of here in 30 minutes.” Or, you may be thinking “Oh no. There are like a million things that can go wrong with a hand. Please tell me hand surgery is in house!” While there is no way to cover everything that can go wrong with the hand, this post will cover some of the most common hand injuries and how to recognize and manage them in the emergency department.

AVNRT

AVNRT is also referred to as paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia (PSVT) or simply supraventricular tachycardia (SVT). However, it is important to understand that SVT is an umbrella term that refers to all tachydysrhythmias that originate above the ventricles including atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter, for example. When describing a supraventricular tachycardia that is due to a re-entrant circuit in the AV node specifically, it is better to use the term AVNRT as opposed to SVT in order to avoid confusion.

Are you sure you wish to end this session?