Revision Resources

Recent Posts View All

April FOAMed

Alcohol Intoxication

Acute alcohol intoxication is often identified early in a patient’s visit by behavioral changes accompanied by slurred speech, ataxia, nystagmus, or the smell of alcohol. However, evaluating and managing patients with acute alcohol intoxication in the emergency department can be challenging. Patients may be agitated or altered, hindering their initial evaluation and diagnostic workup. The situation is more dangerous given the high incidence of chronic disease, critical illness, and acute trauma.

Post-Intubation Sedation

The immediate post intubation period in the ED is a critical time for continued patient stabilization. While physical adjuncts like securing the tube, in line suctioning, and head positioning are part of general post intubation management, a better understanding of analgesics and sedatives have offered newer approaches and improved outcomes down the line during the patient’s hospital stay. The reality of ever increasing ED volumes and longer boarding times to the ICU makes it imperative for emergency physicians to learn how to manage these critical patients.

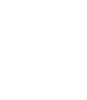

Aortic Stenosis

An 83-year-old female presents to the ED with dyspnea at rest following a syncopal episode. Patient reports she was out for a walk with her husband when she began to feel lightheaded, short of breath, and then fainted. Triage vitals include BP 88/50, HR 115, RR 24, O2 98%. ECG is without signs of acute ischemia. On exam, the patient appears slightly tachypneic, with rales noted at bilateral lungs. There is a systolic murmur along with 2+ pitting edema at the lower extremities. Cardiac POCUS shows grossly decreased left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) with a hyperechoic structure at the aortic valve.

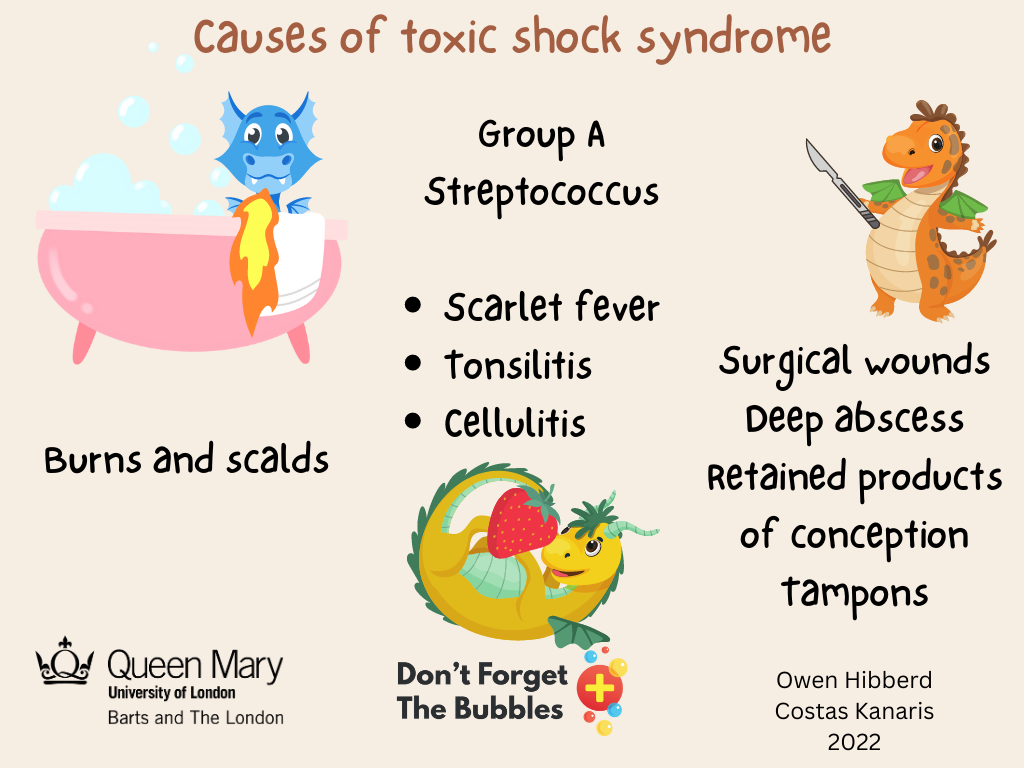

Toxic Shock Syndrome

5-year-old Damon scalded his chest after reaching up to grab a rather appealing hot chocolate. His Mum performed appropriate first aid and the injury was dressed and treated at their local minor injury unit. Unfortunately, Damon has been picking at the wound (a very bad habit). His Mum brings him to the emergency department two days later. He has a rash around the burn, fever, rigors and seems lethargic.

Malignant Otitis Externa

Malignant otitis externa (MOE) is a severe and progressive infection of the external auditory canal. MOE has also been called necrotizing otitis externa and skull base osteomyelitis. First described as a case of progressive Pseudomonas osteomyelitis of the temporal bone in a diabetic patient in 1959. Pathophysiology includes osteomyelitis of the skull base osteomyelitis. MOE begins as an infection of the external ear canal and spreads to the temporal bone and skull base and can affect the jugular foramen and other intracranial structures. Water exposure is often implicated. Prior to the use of antibiotics, MOE had rates of death reported up to 50%. This disease still carries a high morbidity and mortality, with current rates of mortality estimated as high as 20%.

Are you sure you wish to end this session?